今期《經濟學人》的封面主題,是「裙帶資本主義」(crony capitalism)在全球的影響力正日漸上升。根據《經人》所言,所謂裙帶資本主義,是指某些行業如賭博、地產、伐木、能源及礦業等,商人在從事相關 生意之時,必須與政府官員商議地權安排及專營權事宜。在這些商討的過程中,關係與貪污等金權政治容易出現,變相造成不公平的競爭關係,並形成所謂「財閥」 的出現。

《經人》指出,「財閥」透過政治聯繫獲得經濟利益行為,在印度、烏克蘭及俄羅斯等國均非常嚴重。這些國家的建設及開發計劃,大多不透過公開的拍賣或商討分配,而是透過貪污、關係及利益輸送,令一眾財閥取得這些令人垂涎的計劃。《經人》認為,這些「尋租行為」(rent-seeking)對資本主義的長期發展,有百害而無一利。首先,這些行為令財閥得以壟斷資源,並向市民提供劣質或價格過份高昂的公共服務。更重要的是,財閥的壟斷,使有朝氣有活力的新興資本家難以長足發展,形成「金權政治」制度化的不良格局。

香港大有空間出現裙帶資本主義

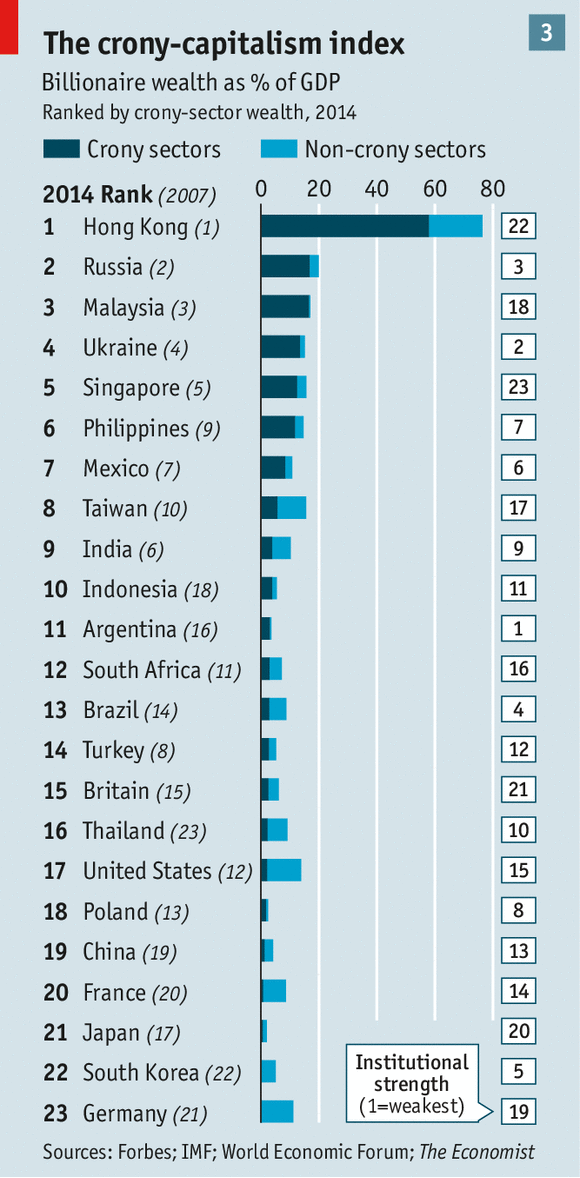

《經人》更特別為此設計了 一個「裙帶資本主義指數」。這個指數的計算方法,是先列出公用事業、地產及電訊等必須與政府合作才能開始生意的行業,然後根據《福布斯》的資料,計算在這 些行業的富豪,到底佔該地的國民生產總值多少,從而推算該地是否容易形成「金權政治」、財閥當道。

令人詫異的是,香港在這個調查中獨佔鰲頭。香港在這些行業營商的億萬富豪總財富,竟佔了香港國民生產總值達60%, 遠遠拋離第二名俄羅斯的18%左右。不過我們必須指出,容易形成「金權政治」,與實質形成金權政治並不相同。以南韓為例,雖然在排名中位列尾二,但當地電 子業巨頭如三星、LG等的政治影響力,可說是舉足輕重。香港方面則雖有不少富豪壟斷公用事業,但因現行法治制度尚算健全,貪污及利益輸送等行為,至少未如 俄羅斯及印度等國般的明目張膽程度。

但無論如何,香港在這個指 數上遙遙領先,其實也是一個提醒,說明香港政府只要在土地安排、資源調配的透明度、以及在清廉程度上保持水準,則香港應能免於金權政治。否則。一旦如紅灣 半島、新界東北等疑似利益輸送的事件不斷出現以至惡化,則香港隨時有潛力是把裙帶資本主義、「金權政治」發揮得最極致的地區。

The Economist: The New Age of Crony Capitalism

Political connections have made many people hugely rich in recent years. But crony capitalism may be waning

AS THE regime of Viktor Yanukovych collapsed in Ukraine, protesters against it could be found outside One Hyde Park, a luxury development in west London. Their target was Rinat Akhmetov, Ukraine’s richest man and a backer of the old regime. “Discipline your pet”, they chanted.

Ukraine’s troubled state has long been dominated by its oligarchs. But across the emerging world the relationship between politics and business has become fraught. India’s election in April and May will in part be a plebiscite on a decade of crony capitalism. Turkey’s prime minister is engulfed by scandals involving construction firms—millions of Turks have clicked on YouTube recordings that purport to incriminate him. On March 5th China’s president, Xi Jinping, vowed to act “without mercy” against corruption in an effort to placate public anger. Last year 182,000 officials were punished for disciplinary violations, an increase of 40,000 over 2011.

As in America at the turn of the 20thcentury, a new middle class is flexing its muscles, this time on a global scale. People want politicians who don’t line their pockets, and tycoons who compete without favours. A revolution to save capitalism from the capitalists is under way.

The kind of rents estate agents can only dream of

“Rent-seeking” is what economists call a special type of money-making: the sort made possible by political connections.This can range from outright graft to a lack of competition, poor regulation and the transfer of public assets to firms at bargain prices. Well-placed people have made their fortunes this way ever since rulers had enough power to issue profitable licences, permits and contracts to their cronies. In America,this system reached its apogee in the late 19th century, and a long and partially successful struggle against robber barons ensued. Antitrust rules broke monopolies such as John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil. The flow of bribes to senators shrank.

In the emerging world, the past quarter-century has been great for rent-seekers. Soaring property prices have enriched developers who rely on approvals for projects. The commodities boom has inflated the value of oilfields and mines, which are invariably intertwined with the state. Some privatisations have let tycoons milk monopolies or get assets cheaply. The links between politics and wealth are plainly visible in China, where a third of billionaires are party members.

Capitalism based on rent-seeking is not just unfair, but also bad for long-term growth. As our briefing on India explains(see article), resources are misallocated: crummy roads are often the work of crony firms. Competition is repressed: Mexicans pay too much for their phones.Dynamic new firms are stifled by better-connected incumbents. And if linked to the financing of politics, rent-heavy capitalism sets a tone at the top that can let petty graft flourish. When ministers are on the take, why shouldn’t underpaid junior officials be?

The Economist has built an index to gauge the extent of crony capitalism across countries and over time (see article). It identifies sectors which are particularly dependent on government—such as mining, oil and gas, banking and casinos—and tracks the wealth of billionaires(based on a ranking by Forbes) in those sectors relative to the size of the economy. It does not purport to establish that particular countries are particularly corrupt, but shows the scale of fortunes being created in economic sectors that are most susceptible to cronyism.

Rich countries score comparatively well, but that is no reason for complacency. The bailing out of banks has involved the transfer of a great deal of wealth to financiers; lobbyists have too much influence, especially in America (see article); today’s internet entrepreneurs could yet become tomorrow’s monopolists. The larger problem, though, lies in the emerging world, where billionaires’ wealth in rent-heavy sectors relative to GDP is more than twice as high as in the rich world. Ukraine and Russia score particularly badly—many privatisations favoured insiders. Asia’s boom has enriched tycoons in rent-seeking sectors.

Wanted: emerging-market Roosevelts

Yet this may be a high-water mark for rent-seekers, for three reasons. First, rules are ignored less freely than they used to be. Governments seeking to make their countries rich and keep people happy know they need to make markets work better and bolster the institutions that regulate them. Brazil, Hong Kong and India have beefed up their antitrust regulators. Mexico’s president, Enrique Peña Nieto, wants to break its telecoms and media cartels. China is keen to tackle its state-owned fiefs.

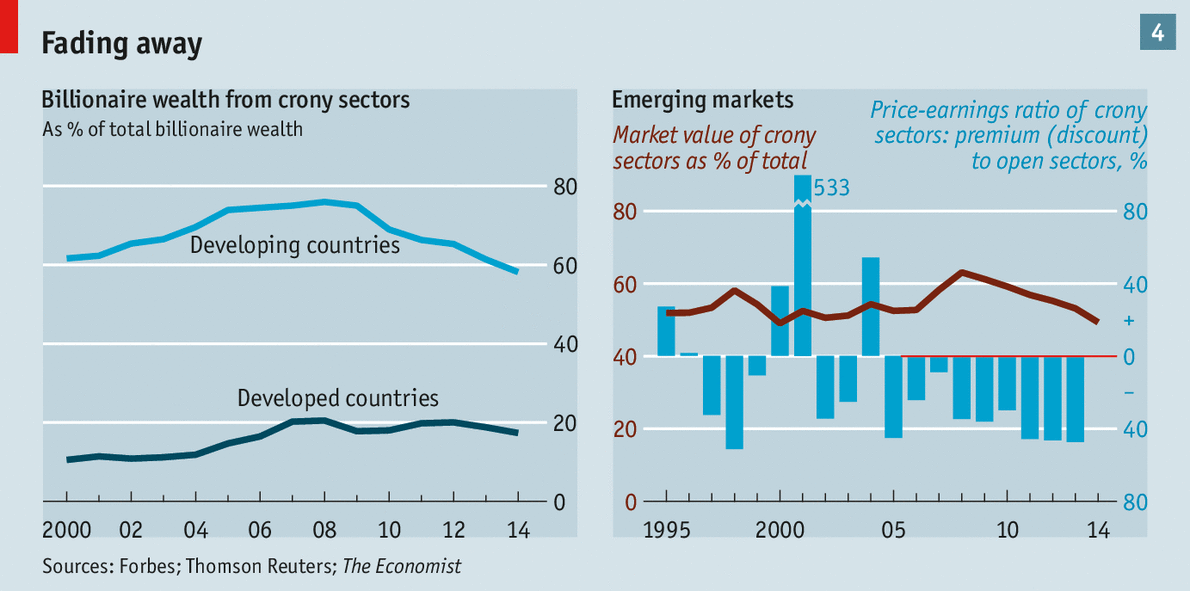

Second, the financial incentives for businesses may be changing. The share of billionaire wealth from rent-rich industries in emerging markets is now falling, from a peak of 76% in 2008 to58% today. This is partly a natural progression. As economies get richer,infrastructure and commodities become less dominant. Between 1900 and 1930 new fortunes in America were built not in railways and oil but in retailing and cars. In China today the big money is made from the internet, not building heavy industrial plants with subsidised loans on land secured through party connections. But this also reflects the wariness of investors: in India, after a decade of epic corruption, industrialists in open and innovative sectors such as technology and pharmaceuticals are back in the ascendant.

The last reason for optimism is that the incentives for politicians have changed, too. Growth has slowed sharply, making reforms that open the economy vital. Countries with governments that are reforming and trying to tackle vested interests, such as Mexico, have been better insulated from the jitters in the financial markets.

There is much more to be done. Governments need to be more assiduous in regulating monopolies, in promoting competition,in ensuring that public tenders and asset sales are transparent and in prosecuting bribe-takers. The boom that created a new class of tycoon has also created its nemesis, a new, educated, urban, taxpaying middle class that is pushing for change. That is something autocrats and elected leaders ignore at their peril.

Our crony-capitalism index

Planet Plutocrat

AMERICA’S Gilded Age, in the late 19thcentury, saw tycoons such as John D. Rockefeller industrialise the country—and accumulate vast fortunes, build palatial mansions and bribe politicians. Then came the backlash. Between 1900 and 1945 America began to regulate big business and build a social safety net. In her book “Plutocrats”, Chrystia Freeland argues that emerging markets are now experiencing their first gilded age, and rich countries their second, with the world’s wealthiest 1%, who benefited disproportionately from 20 years of globalisation, forming a “new virtual nation of Mammon”.

Inventing a better widget, tastier snack or snazzier computer program is one thing. But many of today’s tycoons are accused of making fortunes by “rent-seeking”: grabbing a bigger slice of the pie rather than making the pie bigger. In technical terms, an economic rent is the difference between what people are paid and what they would have to be paid for their labour, capital, land (or any other inputs into production) to remain in their current use. In a world of perfect competition, rent would not exist.Common examples of rent-seeking (which may or may not be illegal) include forming cartels and lobbying for rules that benefit a firm at the expense of competitors and customers.

Class warriors and free-market devotees alike are worrying about rent-seeking. American libertarians fear an elite has rigged their country’s economy; plenty of ordinary Joes reckon the government and Federal Reserve care more about Wall Street than Main Street. Many hedge-fund managers sniff that China is a house of cards built by indebted cronies.

To test the claim that rent-seekers are on the rampage, we have created a crony-capitalist index. Our approach builds on work by Ruchir Sharma of Morgan Stanley Investment Management, Aditi Gandhi and Michael Walton of New Delhi’s Centre for Policy Research, and others. We use data from Forbes to calculate the total wealth of those of the world’s billionaires who are active mainly in rent-heavy industries, and compare that total to world GDP to get a sense of its scale. We show results for 23 countries—the five largest developed ones, the ten largest developing ones for which reliable data are available, and a selection of eight smaller ones where cronyism is thought to be a big problem. The higher the ratio, the more likely the economy suffers from a severe case of crony-capitalism.

We have included industries that are vulnerable to monopoly, or that involve licensing or heavy state involvement(see table 1). These are more prone to graft, according to the bribery rankings produced by Transparency International, an anti-corruption watchdog. Some are obvious. Banks benefit from an implicit state guarantee that lowers their cost of borrowing. When publicly owned coal mines, land and telecoms spectrum are handed to tycoons on favourable terms, the public suffers. But the boundary between legality and graft is complex. A billionaire in a rent-heavy industry need not be corrupt or have broken the law. Industries that are close to the state are still essential, and can be healthy and transparent.

A galaxy of riches

Billionaires in crony sectors have had a great century so far (see chart 2). In the emerging world their wealth doubled relative to the size of the economy, and is equivalent to over 4% of GDP,compared with 2% in 2000. Developing countries contribute 42% of world output,but 65% of crony wealth. Urbanisation and a long economic boom have boosted land and property values. A China-driven commodity boom enriched natural-resource owners from Brazil to Indonesia. Some privatisations took place on dubious terms.

Of the world’s big economies, Russia scores worst (see chart 3). The transition from communism saw political insiders grab natural resources in the 1990s, and its oligarchs became richer still as commodity prices soared. Unstable Ukraine looks similar. Mexico scores badly mainly because of Carlos Slim, who controls its biggest firms in both fixed-line and mobile telephony. French and German billionaires, by contrast,rely rather little on the state, making their money largely from retail and luxury brands.

America scores well, too. The total wealth of its billionaires is high relative to GDP, but was mostly created in open sectors. Silicon Valley’s wizards are far richer than America’s energy billionaires. It is one of the few countries where rent-seeking fortunes grew only in line with the economy in recent years, which explains its improved position since 2007. Despite concerns about vampire-squid financiers, few of its billionaires made their money in banking. Even including private equity as rent-seeking, on the grounds that it benefits from tax breaks and cheap loans,would make little difference. Compared with Larry Ellison of Oracle, Stephen Schwarzman of Blackstone is a pauper.

Countries that do well on the crony index generally have better bureaucracies and institutions, as judged by the World Economic Forum. But efficient government is no guarantee of a good score: Hong Kong and Singapore are packed with billionaires in crony industries. This reflects scarce land, which boosts property values, and their role as entrepots for shiftier neighbours. Hong Kong has also long been lax on antitrust: it only passed an economy-wide competition law two years ago.

Another surprise is that despite its reputation for graft, mainland China scores quite well. One reason is that the state owns most natural resources and banks; these are a big source of crony wealth in other emerging economies. Another is that China’s open industries have fostered a new generation of fabulously rich entrepreneurs, including Jack Ma of Alibaba, an e-commerce firm, and Liang Wengen of Sany, which makes diggers and cranes.

One of the most improved countries is India,which moved from sixth place in our ranking to ninth. Recent graft scandals and a slowing economy have hurt many of its financially leveraged and politically connected businessmen, while those active in technology, pharmaceuticals and consumer goods have prospered. Turkish billionaires in rent-seeking industries have been hit by their country’s financial turmoil. By contrast most countries in South-East Asia, including Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines, saw their scores get worse between 2007 and 2014, as tycoons active in real estate and natural resources got richer.

Who are you calling a crony?

Our crony index has three big shortcomings.One is that not all cronies make their wealth public. This may be a particular problem in China, where recent exposés suggest that many powerful politicians have disguised their fortunes by persuading friends and family to hold wealth on their behalf. Unreliable property records also help to disguise who owns what.

Second, our categorisation of sectors is crude. Rent-seeking may take place in those we have labelled open, and some countries have competitive markets we label crony. Some think America’s big internet firms are de-facto monopolies that abuse their positions. South Korea’s chaebol, which sell cars and electronics to the world, are mainly in industries we classify as open. But they have a history of bribing politicians at home. China’s billionaires, in whatever industry, are often chummy with politicians and get subsidised credit from state banks. According to Rupert Hoogewerf of the Hurun Report, a research firm, a third are members of the Communist Party. Sectors that are cronyish in developing countries may be competitive in rich ones: building skyscrapers in Mumbai is hard without paying bribes, and easy in Berlin. Our index does not differentiate.

The third limitation is that we only count the wealth of billionaires. Plenty of rent-seeking may enrich the very wealthy who fall short of that cut-off. America’s subprime boom saw hordes of bankers earn cumulative bonuses in the millions of dollars, not billions. Crooked Chinese officials may have Range Rovers and secret boltholes in Singapore—but not enough wealth to join a list of billionaires. So our index is only a rough guide to the concentration of wealth in opaque industries compared with more competitive ones.

Despite the boom in crony wealth, there are grounds for optimism. Some countries are tightening antitrust rules. Mexico has many lucrative near-monopolies, from telecoms to food, but its government is at last aiming to improve regulation and boost competition. India’s legal system is trying to jail a minister accused of handing telecoms licences to his chums.

Encouragingly, there are also hints that cronyism may have peaked. The share of billionaire wealth from rent-seeking industries has declined in developing countries, from a high of 76% in 2008 to58% (see chart 4). That partly reflects lower commodity prices. But now that emerging markets are slowing, investors are becoming pickier. More are steering clear of firms in opaque industries with bad governance. The price-earnings ratio of firms in crony sectors is now at its biggest discount to firms in open sectors for 15 years. That suggests that the highest returns to outside investors are to be found in open industries.

Perhaps when growth picks up again in emerging markets, rent-seeking will explode once more. Or, as countries get richer, the share of great wealth that is made in crony industries may naturally decline. In 1900 American tycoons became rich by building and financing railroads. By 1930 the action had shifted to food production,photography and retailing. Cronies around the world should take note.